Many people talk of the professionalisation of charities. Where once people joined local membership organisations, as Theda Skocpol argues, they now “send checks to a dizzying plethora of public affairs and social service groups run by professionals.”

Group members seem to have evolved into donors, with fewer volunteers, and more paid, policy focused staff.

Or so we’re told.

Recent literature has struggled to find widespread evidence of this trend. Could it be that the perceived professionalisation trend is merely a figment of our imagination?

I set out to answer this question in 2021, with a research essay for which I received a High Distinction (92%).

Data wrangling

To investigate these trends I used the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission’s annual Charity Register data. I combined seven years of these data sets to view trends within organisations over the period.

To identify which charities in this dataset were civil and interest groups, I initially used a list of such groups provided in previous research. I used the Australian Governments ABN Lookup API to retrieve each group’s business number which could then be used as a primary key to identify the group in the dataset.

This was later replaced with a list of the organisations business numbers provided by Professor Halpin. This was more accurate, as some groups business names were not similar to their trading names, preventing the API from finding an accurate match.

Data analysis

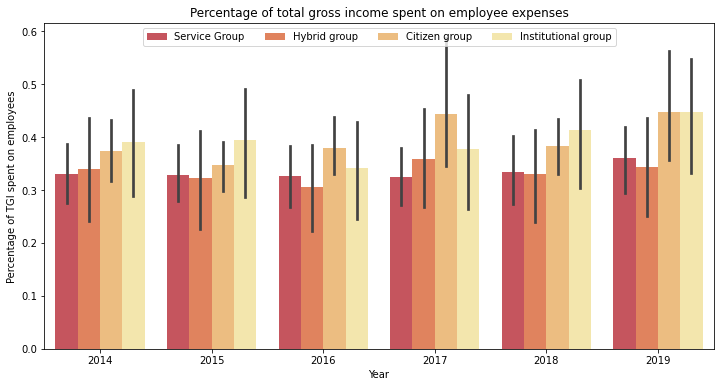

Once the civil and interest groups had been identified and the data sets cleaned, I conducted analysis on the groups to identify trends of increasing staff head counts and decreasing in volunteer numbers.

I used the Mann Kendall test to determine whether there were statistically significant increases in either of these factors over time. I used Seaborn to visualise the results in Python.

You can see my code here.

The results

So what do the results say?

In short, the data suggests that charities are hiring more professional staff than one would expect from increases in their income alone. But does this mean they are becoming increasingly professionalised?

Well, not really.

Firstly, the increase is at such a low rate of growth that it does not seem like an indicator of a boom of professionalisation similar to one that Skocpol observes in the 1960s.

Secondly, spending more on staff doesn’t necessarily mean an organisation is becoming more professionalised. For all we know, these staff members could be hired to better engage with members of the organisation.

And would it be such a bad thing? Organisations need efficient staff to be effective. Bang-for-buck is important, but the percentage of total income spent on staff is a crude way to measure this. GiveWell do a better job at estimating organisational effectiveness than I ever could.

None-the-less, this work does reveal interesting trends in the staffing levels of interest groups that are not yet fully understood. With further research in the area, we may uncover new contemporary trends in the interest group system.